Many patients don’t want value-based Care

Orthopedic Business Review

written by Will Kurtz, M.D.

August 18, 2024

Introduction

Don’t get me wrong, I like value-based care (VBC). Most musculoskeletal (MSK) physicians (myself included) feel a fiduciary responsibility to provide their patients with VBC recommendations, but physicians who give patients the immediate care they want often earn better reputations than VBC physicians.

VBC recommendations often upset MSK patients, and patients rarely express appreciation for VBC recommendations because VBC recommendations often prioritize finances over the patient’s MSK pain. Most patients want immediate action, and VBC often means waiting on MRIs and procedures to see if the MSK problem auto-corrects. In our world of immediate gratification, our phones can instantaneously answer all of our questions, so why can’t our physicians order an MRI to determine why our knee hurts? When physicians recommend a wait and see VBC approach, they can be seen as uncaring or disinterested. Recommending VBC can be frustrating for physicians as well. VBC physicians think they are looking out for their patients’ best interests, but patients are often disappointed in the lack of care they receive and go elsewhere.

In this blog, we are going to discuss:

How some MSK physicians and patients are directly and indirectly motivated to seek inappropriate MSK care and how it is difficult to determine who is to blame for the inappropriate care (attribution).

How many MSK problems are readily discussed among friends and researched on the internet, which leads to patients developing their own preconceived treatment plan before they visit their MSK physician.

How patients’ preconceived treatment plans can increase inappropriate care. Patients get the care they want through doctor-shopping.

How physicians who recommend inappropriate care are seen as more compassionate and get more patient referrals.

Lastly, we will offer some recommendations on how to lower MSK spending through early patient education.

If you are a practicing VBC physician, I am sure you will agree with much of this discussion. If you are a healthcare outsider trying to disrupt the system with VBC, you need to understand how patients inadvertently and sometimes willfully increase inappropriate care if you want to successfully lower MSK spend.

This discussion may be unique to MSK care. Most MSK care is elective, which gives patients the opportunity to doctor-shop to find a physician who agrees with the patient’s preconceived treatment plans. MSK physicians often have conflicting ideas about the appropriateness of MSK care. Patients often have strong preconceived ideas about their MSK care that are usually contrary to VBC, which influences physicians’ treatment recommendations.

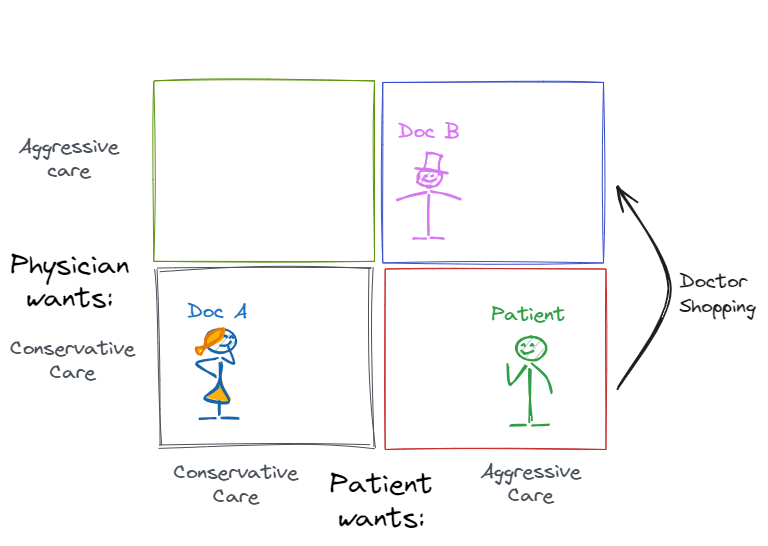

Attribution of inappropriate care

In order to discuss the attribution of inappropriate care, I have created two diagrams. The first diagram helps explain how inappropriate care can be divided into two categories: the person asking for the care and their motivation (Fig. 1). Direct motivation is the hardest behavior to change because the participants do not want to change. Indirect motivation is easier to change because the participants just need to be informed of the consequences of inappropriate care.

Fig. 1 - Motivations behind physician- and patient-driven inappropriate care

The Green Box

The media typically blames inappropriate care on physicians who are directly motivated to provide inappropriate care for financial gains (i.e., the green box). Healthcare physicians can be directly motivated through fee-for-service to increase the consumption of all healthcare, both appropriate and inappropriate. Recommending a procedure takes less time in the clinic than discussing why a procedure may be unnecessary and can create downstream revenue. Busy physicians may not take the time to have a VBC discussion. Many MSK physicians own ancillary services and may refer patients to those ancillary services more often. As more and more physicians hang out in this green box, it becomes more socially acceptable to practice MSK care in the green box. Most green-box physicians do not think of themselves as outliers and will usually correct their inappropriate care when they are shown data that proves they are an outlier, as shown in Marty Makary’s book, The Price We Pay.

The Blue Box

The physicians in the blue box generally have the best reputation among patients. They are your concierge doctors. Patients often feel like these doctors are more caring because they recommend more tests and procedures. Patients feel like they are heard and that something is being done about their MSK problems. Some physicians in this blue box may also order tests to protect themselves from litigation.

Most physicians order inappropriate care because it is good customer service to give patients what they want when they want it. Physicians appear more caring when they overtreat compared to when they undertreat. Appropriate VBC care can be harder, more time-intensive, and more toxic to the doctor-patient relationship. Physicians can avoid long wait times in their clinics if they just order the unnecessary test that a patient requests rather than take the time to explain why that test is inappropriate.

Many patients secretly want inappropriate care but do not want to be viewed as seeking inappropriate care. As a practicing MSK physician, I always try to provide my patients with an appropriate recommendation (NSAIDs and PT) and an aggressive recommendation (immediate MRI). I often tell patients that their MSK problem should be self-limiting, their pain should dissipate, and their function should return to normal in a few months, but that an immediate MRI is an option if they want it. I tell them the MRI is likely a waste of their money. I pause after delivering these two options to allow the patient to indicate which option they want. About a third of patients just admit they want aggressive treatment, and a third just want appropriate treatment. The other third sits in silence. They want the aggressive and inappropriate option, but do not want to ask for it.

This scenario begs the question: Who are physicians supposed to serve? Are physicians supposed to give their patients the best MSK experience, the MSK experience that the patient wants, or are physicians supposed to serve the plan sponsor with the lowest MSK spend (VBC)?

Obviously, the same physician can exist in the green box for some treatment recommendations and in the blue box for other treatment recommendations. Attribution of inappropriate care is hard if you are not present for the clinic conversation or have some insight into the physician’s motivation. Is the patient demanding an MRI scan, or is the physician ordering an inappropriate MRI scan to increase their ancillary revenue? Many companies analyze claims data to try to determine a physician’s motivation, but the attribution of inappropriate care is still a challenge.

The Grey Box

Patients can be financially incentivized to consume more healthcare care. Workers compensation, military compensation and pension injuries, and motor vehicle accidents can increase the patient’s financial payout if they choose surgery or other aggressive care. When a patient in the grey box meets up with a MSK surgeon in the green box, MSK care is likely to be consumed at a higher rate.

The Red Box

Many patients present to their MSK physician’s office with their own preconceived treatment plan, like “I need an MRI.” Patients often believe that more MSK care is better MSK care. Patients may feel that being proactive with their healthcare is a wise decision and fail to realize how overindulgence in inappropriate healthcare can cause worse outcomes. Some patients think more expensive care is better care. A Veblen product is where, as the price increases, the demand for the product also increases, like a Hermes Birkin bag. Some patients still believe quality follows price in healthcare, which is definitely not true. Some patients also view their healthcare premiums as a sunk cost fallacy. Patients pay thousands of dollars towards their healthcare benefits and feel like they should consume as much healthcare to get their money’s worth for their healthcare plan premiums.

MSK injuries are visible and therefore openly discussed among colleagues. When someone walks into work on crutches, their colleagues often share their own MSK stories. MSK injury stories often reflect positively on patients, so colleagues can talk about the injury without slandering their friend (narrative bias). For instance, Bob was skiing at an exclusive resort when he tore his meniscus. Bob looks good, even though something bad happened. The people in Bob’s office who have also torn their meniscus are going to tell Bob that he must go to their surgeon because he/she is the best. As a result, surgeons who operate more get more referrals over time.

MSK injuries are easily researched online, which also helps patients develop a pre-conceived treatment plan.

Resolving Differences in Treatment Plans

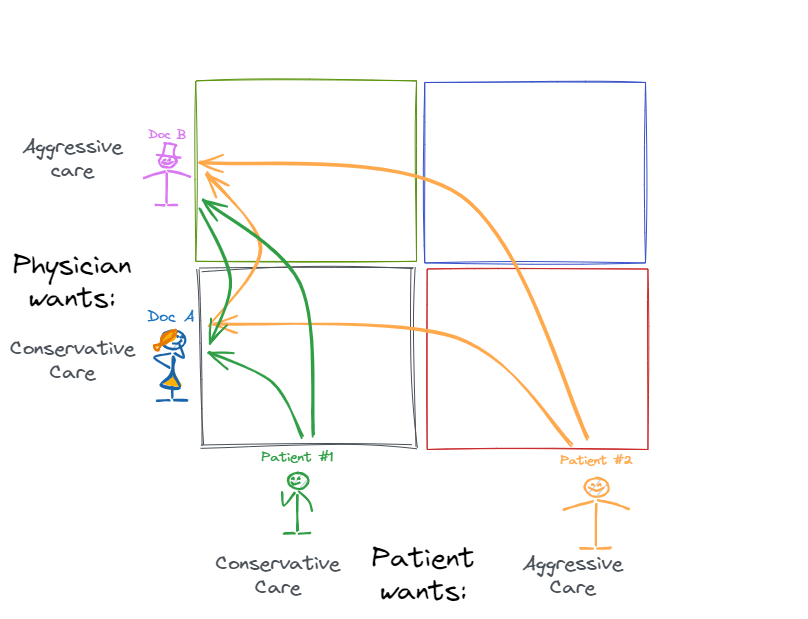

Our second diagram looks at how physicians and patients resolve their differences in desired treatment plans. Shared decision-making means both the physician and patient get a vote on what happens. Pundits probably think physicians control MSK treatment plans, but that is often not the case.

The Black Box

If the physician and the patient both want conservative care, then conservative care happens (Fig. 2, black box). For example, a patient on a high-deductible plan sees a physician who discusses different treatment options and the financial implications, and they choose conservative care.

Fig. 2: The causes of aggressive care

The Blue Box

If the physician and the patient both want aggressive care, then aggressive MSK care typically happens unless the insurance company prevents it with prior authorization. For example, a work comp patient may receive a larger settlement if they have surgery, and surgeons get paid more for work comp surgeries than other carriers, so work comp injuries result in more surgeries.

The Red Box

Opportunities to lower MSK costs exist when the physician and patient disagree on the aggressiveness of the treatment plan.

In the example below, we have a theoretical doctor (Doc A) and a patient. The doctor recommends conservative care, but the patient wants aggressive care because their friends told them they need an MRI and a knee scope (i.e., aggressive care). For this blog, I am defining aggressive MSK care as something that increases expenses but is not harmful, like ordering an MRI. Obviously, if the aggressive MSK care is potentially harmful, like a CT scan (radiation) or an unnecessary surgery, then the physician should stand their ground and refuse to do something that harms the patient.

Fig. 3

Doc A initially recommends physical therapy (PT) and NSAIDs, to which the patient says, “I want a knee MRI first.” Doc A lays out a reasoned explanation for why they should try PT first, and the patient leaves with a PT script in hand and feels like Doc A does not care about them or their knee pain. The patient then calls their friend who had a similar injury, and their friend says, “I will get you in to see my doctor right away.”

Fig. 4

Doc B then sees the patient. Doc B might have recommended conservative care under a different circumstance but orders the MRI when the patient tells Doc B, “Can you believe that Doc A was so dismissive as to not even order a knee MRI?” Doc B reads the room, orders the MRI, and follows that up with a knee scope. In this example, the patient gets the aggressive care they want, Doc B gets a 5-star Google review, and Doc A gets a 1-star Google review for “not listening or doing anything to help the patient get better.”

Now, let’s discuss how a conservative doctor A might successfully convince a patient to try conservative care first.

Fig. 5

Patient education can sometimes convince patients that conservative care is better for reasons beyond financial issues. Patient education works best if the patient has not already formulated a treatment plan by talking to their colleagues or researching the internet. After a patient’s colleagues recommend aggressive MSK care, the patients are often anchored to that aggressive treatment plan. It is difficult to convince these anchored patients to try conservative care first.

Providing written information about conservative care is often better received by patients than a verbal lecture about why the patient’s request for an immediate MRI is unwarranted. When I discuss conservative care with a patient, it can feel like I am attacking their preconceived aggressive treatment plan, which is personal. When I give a patient written information with clinical references to studies that support conservative care, it is more objective because the written educational material was produced for a general audience and not a personal attack. Despite trying to steer the patient towards conservative care, I would rather order an unnecessary MRI than have the patient seek care from an aggressive physician. At least, I might have the opportunity to discuss the MRI findings and prevent an unnecessary surgery.

Healthcare plan designs can theoretically incentivize conservative care. Patients can be responsible for more of their healthcare costs through a high-deductible plan, but these HDHP have not lowered healthcare spending, just increased patients’ medical debt. Patients are unaware of the financial consequences of their medical decisions because there is no cost transparency.

Some health plan designs make the physicians responsible for the healthcare cost through surgical bundles, condition-based bundles, or capitation, but these plans have very small market share.

The Green Box

When a physician recommends aggressive care and a patient wants conservative care, some patients can be convinced to proceed with aggressive care. Some patients seek a second opinion. This information asymmetry can allow a physician to abuse the trust placed in the doctor-patient relationship. Artificial intelligence could correct this information asymmetry, as we will discuss below.

Fig. 6

Many patients will leave the doctor’s office and then cancel the aggressive care days later or seek a second opinion.

Fig. 7

Doctor shopping results in MSK patients getting the MSK care they want and not the MSK care that the first physician recommends. Doctor shopping can increase inappropriate care (Fig. 4) or decrease inappropriate care (Fig. 7). Patients’ preconceived treatment plans usually involve more MSK care instead of less MSK care, so doctor shopping will usually increase MSK care spending.

A Statistical understanding of Doctor Shopping

Doctor shopping is well known among narcotic-seeking patients who shop around to multiple physicians to find someone to prescribe their narcotics. Similarly, patients with a preconceived MSK treatment plan often shop around to find a MSK physician who agrees with their treatment plan. This is a form of confirmation bias. In order to understand how impactful doctor shopping can be on inappropriate care, we need to review a statistical term called the “at least once” rule.

What are the odds of a coin showing heads at least once, if you flip it four times?

Fig. 8

The “at least once” rule looks at the likelihood of the opposite event occurring with each trial and the number of times the trial occurs. The likelihood of tails is obviously 0.5, so the likelihood of heads appearing at least once over 4 coin flips is (1- (0.5 * 0.5 * 0.5 * 0.5) = 93.75%. In other words, the likelihood of flipping tails 4 times in a row is 6.25% or 1/16.

What are the odds of my kids getting candy if they ask their mom and me separately?

Fig. 9

Let us assume that I am a pushover and say “yes” 70% of the time. My wife, on the other hand, is more strict and says “yes” only 20% of the time. The likelihood of me saying “no” is 0.3, and the likelihood of my wife, mom, saying “no” is 0.8. The likelihood of one parent saying “yes” and the kids getting their candy is 1 minus (0.8 * 0.3) = 76%.

So let’s use the “at least one” rule to discuss inappropriate care. What are the odds that a patient will get their preconceived treatment if they get opinions from two different doctors? For this example, we will have two theoretical physicians (Doc A and Doc B) and two theoretical patients (Patient 1 and Patient 2).

Let’s assume Doc A is conservative and recommends aggressive care 10% of the time. Doc A is low on the Y axis. Doc B is aggressive, recommends aggressive care 80% of the time, and is high on the Y axis. Patient 1 prefers conservative care and is low on the X axis. Patient 2 prefers aggressive care and is high on the X axis. For this example, we will assume that if the doctor recommends a treatment that the patient does not want, then the patient will seek a second opinion. We will also assume that Patient 1 and Patient 2 have the same MSK problem that could be properly treated conservatively or aggressively.

Fig. 10

When Patient 1 sees both doctors, the likelihood of getting the conservative care they want is 1 minus (0.1 * 0.8) = 92%. When Patient 2 sees the same two doctors, the likelihood of getting the aggressive care they want is 1 minus (0.9 * 0.2) = 82%.

Aggressive care occurs against Patient #1’s wishes only 8% of the time. Conservative care occurs against Patient #2's wishes only 18% of the time. These already low percentages will be even lower when you consider that the second doctor is going to realize the patient is seeking a second opinion because the first doctor did not recommend the treatment the patient wanted (response bias). Patient #1 received aggressive care 8% of the time, compared to Patient #2’s 82% of the time. The patients’ preconceived treatment plan causes a 10-fold increase in the prevalence of aggressive care with the same MSK problem and the same two doctors.

The power of referrals from aggressive care

Physicians who recommend aggressive care get more referrals than non-aggressive physicians because improvement from aggressive treatment is attributed to physicians and improvement from non-aggressive treatment is attributed to physical therapists and the self-healing of patients.

Fig. 11 - More surgeries creates more referrals

Other biases in MSK care

Needing MSK care is not shameful, and therefore it is openly discussed among patients and their friends. MSK care is visible. Patients limp and use braces that get noticed and start discussions. Patients with many medical diagnoses, like lung cancer, do not discuss their problems with friends and, therefore, do not formulate a preconceived treatment plan. Many MSK patients openly discuss their MSK problems and formulate a preconceived treatment plan that is often more aggressive than what a VBC physician would recommend. This leads to a narrative bias where MSK care is discussed more than other forms of healthcare, and operative MSK treatments are discussed more than non-operative MSK treatments. Surgeons who operate more are recommended more than surgeons who operate less.

Patients often feel like being proactive with their health is better, which often leads to the idea that more healthcare is better healthcare (vitamin bias). Some patients think getting a small MSK surgery now may prevent a larger MSK surgery later, a fact that is often not supported in the literature.

Aggressive care can offer patients some positive reinforcement. It validates the patients’ problem, provides patients with hope for a faster recovery, and allows patients to play the victim among their friends and family.

Future Ideas

Artificial intelligence (AI) could solve the information asymmetry between physicians and patients, as discussed in Fig. 6. I have an AI app on my phone that records my clinic conversations with my patients and creates a clinic note 10-15 minutes after the visit. In the future, patients could have a similar AI app on their phone that will listen to the physician’s conversation and then immediately provide the patient with appropriate follow-up questions to ask their physician during their clinic visit. The app could prompt the patient to ask if there are any alternatives to aggressive treatment plans or if there is any harm in trying conservative care first. This application of AI would be ideal because it could improve knowledge transfer between the physician and patient without deciding treatment recommendations. Chris Dixon calls this AI use a fault-tolerant UX, where the patient can interpret the AI’s prompts, incorporate that information into a discussion with the physician, and not necessarily accept the AI’s recommendation as a final decision. Transcriptions of clinic visits could also help physician rating companies with determining the attribution of inappropriate care.

VBC companies and capitated physicians need to educate patients about VBC MSK care immediately after their injury and before the patient is anchored on aggressive MSK care. This patient education could happen through social engineering using many social media apps.

Take home points:

Many patients arrive at their MSK visit with a preconceived treatment plan, which greatly impacts how their care is delivered.

Physicians should avoid preaching VBC recommendations to patients who want aggressive care. Listen to your patients. Validate their concerns. Present them with options. Otherwise, these patients will doctor-shop and go elsewhere.

Lowering MSK spend through more appropriate MSK utilization starts with providing patients with written, non-confrontational, evidence-based patient education immediately after their MSK injury and before they are anchored on aggressive care.

If you like this article, please read some of my other articles.